Landscape Cities: Why flourishing nature is essential in urban spaces

With the UK’s Planning and Infrastructure Bill sparking backlash over weakened environmental protections, Andrew Grant, founder and director of international landscape architecture practice Grant Associates, shares a vision for thriving cities rich in nature.

The natural world provides us with our fundamental requirements for life – air, water, food, mental stimulation, contact with other species and unlimited inspiration. And yet, we almost entirely ignore these in the way we fund, plan, design and manage our urbanised world.

Could it be that cities need to be defined less by their buildings and more by their life support systems and especially their living landscapes and nature?

Why Landscape Cities?

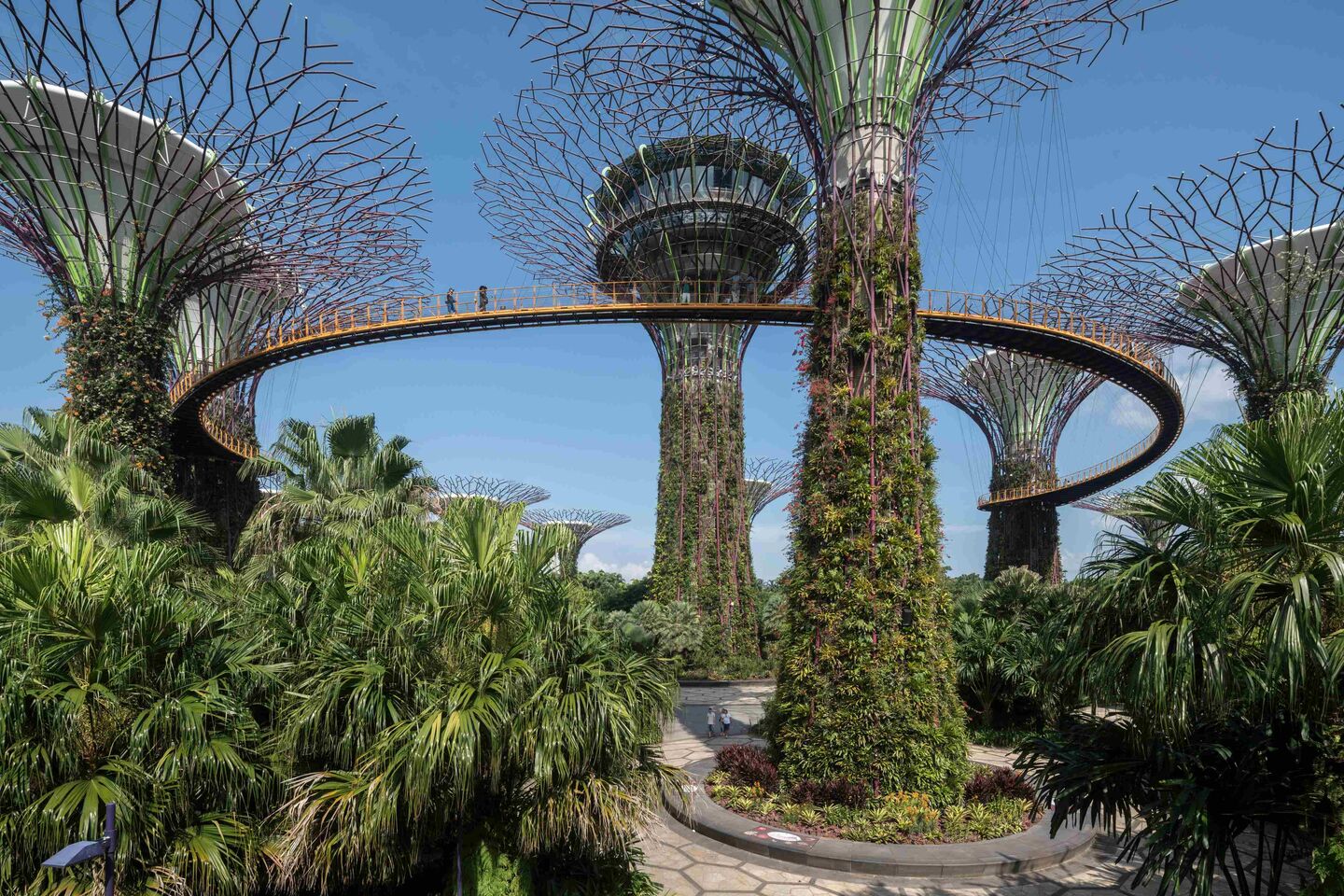

Imagine a world where cities are defined not by architecture, but rather by landscape and ecology. Where species-rich habitats form a connected and colourful web across the city, and where every resident, worker and visitor feels immersed within a healthy living and productive environment as soon as they step outdoors.

Within any ten-minute walk, everyone would be guaranteed to encounter at least seven distinctive landscape and nature experiences – whether they be an urban wildwood, a species-rich grassland, a waterfall, a shaded wood, an urban farm, a rain garden or a rooftop forest. These would be ‘Landscape Cities’ bringing benefits to human economy, health and happiness, and to ecological diversity and resilience.

Landscape Cities are cities where the physical and/or perceived expression and extent of landscape and sense of nature outweighs the scale and extent and influence of buildings and built infrastructure. They are where the functional, ecological, and experiential qualities of landscape primarily define the identity of that city and where the communities who live in and visit that city are inspired by, and value, that landscape city environment.

We can start this transformation by remembering we are beings of nature. The beauty we see in nature stems from a place of survival. Our landscapes of human origin, forests, wetlands and savannahs, provided food and water which we have adapted to perceive as beautiful and good places to inhabit.

Landscapes are also predominantly living environments. They always deliver contact with weather, seasons, day and night and all the realms of biodiversity in nature.

They might be beautiful or unsightly, unpredictable, potentially dangerous, layered with wonder, memories and the unknown. They are our connection to times past and future. Landscapes and the nature they support create a particular sense of place and identity, and are essential to more sustainable cities.

The imperative challenge is to begin the transformation of every piece of urban landscape into a form that best supports the survival of the human race and biodiversity of species. This new urban landscape will increasingly provide our life support system, not just for air, water and food. It must also become our refuge for creative inspiration and a catalyst for imagination.

For these reasons, landscape and nature have to become essential parts of the foundations of future city investment, planning, design and management.

The world is moving into a phase when landscape design may well be recognised as the most comprehensive of the arts. Man creates around him an environment that is a projection into nature of his abstract ideas. It is only in the present century that the collective landscape has emerged as a social necessity. We are promoting a landscape art on a scale never conceived of in history.

Humans are part of nature

We are all Bloody Animals…it’s really weird that with all our technology, with all our instruments, with all our intelligence, still we are really basic.

As designers with nature, we must look for the potential to enrich a place with diversity of species but also to shape it so humans can co-exist and draw inspiration, wonder and joy in the experience of that place.

We also have a duty to go beyond the confines of our project site boundaries and to join forces with those desperately trying to slow or halt the extinction of species. As the Brazilian landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx said: “It seems to be almost an obligation of the landscape architects to combat destruction and to preserve certain ill-fated species in danger of extinction in order that they survive for the education and enjoyment of future generations.”

If our role in the creation of Landscape Cities is to design for the experience of landscape alongside conservation of the natural world, then we must start with an understanding that biodiversity underpins the functions of ecosystems on which we depend for our food and fresh water, and provides the resilience and flexibility of the living world as a whole.

We are literally a part of this living system and we need to develop a language and approach that treats biodiversity and the enhancement of nature in cities as a fundamental requirement and does not suggest biodiversity is an option, to be embraced or not, depending on your particular point of view.

Landscapes of imagination

Landscape Cities will also need to develop new types of inspirational urban landscapes alongside the more conventional spaces allowed for recreation, gardening, food production, and so on. These new landscapes should be designed to evoke a sense of primal landscape and to encourage creative thoughts. They can be permanent or temporary, super scaled or tiny, but their purpose should be to offer a variety of particular places that reconnect us with the wonder, moods and meaning of raw nature whilst offering memorable experiences.

Wildness is synonymous with inspiration and contemplation. Aristotle, Shakespeare, Shelley, Einstein, Beethoven and Attenborough have all used elemental nature as a source of inspired thought. It could be suggested that we all need wildness in our daily lives to feed our imagination, just as we need vitamins to sustain our bodies.

Charles Darwin recognised this need and made his own famous Sand Walk at Down House in Surrey, England. This provided him with a five-minute walk that passed through a formal garden, an open meadow and the dark heart of a wood. This was his choice of place to think and be inspired by the natural world around him. This was his ‘Landscape of Imagination’: it inspired him towards one of the greatest discoveries of all time.

Steve Jobs, the co-founder of Apple, had a similar view on the daily importance of walking through diverse and inspirational landscapes as a way to improve his sense of happiness, productivity and creativity.

However, in modern times, we have planned our cities around function and commerce. Nature is seen more as commodity to harvest, to set the scene, to provide air and water and food – but not as a fundamental part of our existence and certainly not as a source of natural wonder and inspiration.

Wild at heart

Ultimately, Landscape Cities will only emerge if we all accept the need to inject a sense of natural wildness into our daily lives.

We can start by making sure every new city, regenerated city or redeveloped neighbourhood is built around a ‘Wild Heart’ - a space that evokes the heartbeat of nature and all of its qualities.

A space that reconnects us all to the natural rhythms and wonder of the planet.

First published on edie.net